By Noel Ihebuzor

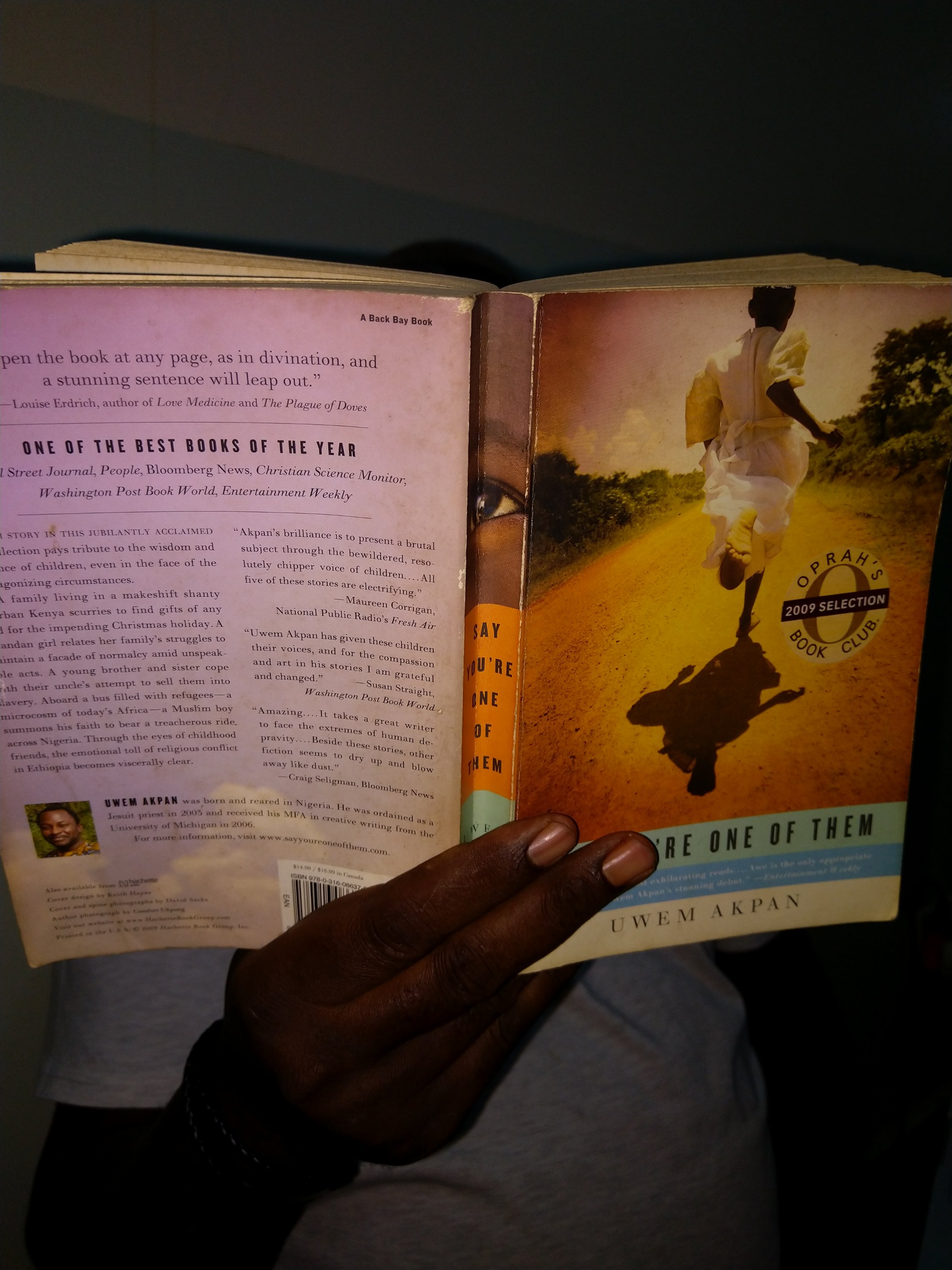

“The thing around your neck”, TTAYN for short, is a collection of 12 short stories told by a writer with an eye for relevant detail, a good understanding of the human mind, and an admirable sensitivity to the sociological context in which her characters operate. The writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, is also capable of plenty of empathy for a majority of the characters in the twelve stories in her book as they struggle to respond to the challenges that life throws at them and make meaning of their varied existence, caught up as they are in specific moments of history as persons with some forms of agency. For a few other characters, she displays a very poorly concealed contempt for their actions and the false lives they lead trying to be what they cannot be. For such characters, she deploys her rich arsenal of sarcasm and irony to ridicule their fake lives underscoring in the process her commitment to people being true to themselves and to their identities.

The stories cover a broad range of topics and issues from the Nigerian-Biafra war, to post-civil war challenges, to life in Nigerian universities and the plague of cultism in them, to wrong practices in academia and to the lives of Nigerians livingin the USA. A few of the stories touch on the lives of married couples whilst some others touch on relationships involving persons with sexual orientations that deviate from the norm and the pains and frustrations that do accompany such. Some other stories touch on themes of violence such as the killings in the north of Nigeria – killings caused by a blend of ethnicity and religious extremism, whilst others explore a broad array of themes spanning the early encounter of Igbo society with white colonization and its agents, especially the Christian missions, agents of evangelization and colonization, to the rigors involved in applying for an American visa in Nigeria, to repressive regimes in Nigeria, to gender and race based inequities and injustices, to sibling rivalry in an environment tainted by patriarchy and contestations of such social structures and strictures, such contestations often giving rise to very bizarre consequences.

Through these short stories, Chimamanda explores a number of themes ranging from political violence and repression, sexual orientation, ethnic killings, marital infidelity, migration and its stresses, coping with loss, racial biases, unequal and unrequited love and its pains, the physical challenges and humiliation that often accompany visa applications, the stresses of marriage in a foreign land and finally to the inadequacies in colonial historiography. She also uses her story to point out ethical and moral failures in the banking sector, where banks use young girls in their marketing divisions to bait rich randy men and potential depositors. Here we note the subtle and not too subtle critique of the abuse of financial power by rich men who exploit power asymmetries in their favor often to take advantage of young female bank workers in age-inappropriate sexual engagements. Chimamanda thus uses her short stories to criticize these and other vices in society. Specifically, she comes against the use of financial power to secure sexual favors. The same criticism of the abuse of power, masking as cultural imperialism, would again show up in her treatment of the manner in which Edward, a white man, tries to exploit his role as workshop convener to impose his views on aesthetics on a creative writers’ workshop, and even to making obtuse sexual advances to some of the female participants at the workshop, again bringing up in the process the intersection of power and gender.

These stories are not single stories, with one story line and a predictable ending. Most of them are richer than comprising a number of interlaced themes and reflecting in many instances a number of intersectionalities, such as those between gender and power, between social class and choices in marriages, between traditional institutions and modern day living and many more. It is this intersectionality that makes her tales very plausible and real. It also makes her characters to come across as people of flesh and blood that the reader can relate to. The stories are so engaging that the reader finds it difficult to put down the book until one has read the last chapter. The beauty of her writing comes alive when we start examining each of the twelve short stories that make up the collection.

Cell One is a presentation of cultism in Nigeria’s tertiary education establishment. The story is built around Nnamabia, the son of a lecturer at Nsukka who progresses from small time pilfering at home to full time criminality and to violence soaked in chilling cultism. The story is told by his sister, who resents the disproportionate attention and privileges that are accorded Nnamabia by their parents. What is sad is the way and manner that Nnamabia’s mother prefers to live in denial and to protect her son even when all the facts before her are pointing to one conclusion. There is an implied criticism of male child preference by parents as this is what partially explains for Nnamabia’s mum turning her eyes away from his criminal activities. The story also broadens to include a strong critique of our policing system, the incarceration of persons in cramped unhealthy cells, the practice of the arrest of a person whose son or relation has committed an offense and the holding of that person until the actual offender shows up.

There is also a level of covert didacticism running throughout the story and it is this. Cultism is bad news for the young one who joins as well as for the families of persons who get drawn into its crippling embrace. The message that comes across is that whereas being a cult member can bring the person a sense of power and connectedness in the short term, in the long term, it brings misery and suffering, apart from its deleterious effects on one’s morals and one’s consciousness which cultism deadens.

Imitation, the next story is a story of love, deception and cheating. It examines the pains and difficulties of long-distance marriages where one of the partners lives in one continent and the other partner lives in another. The story is built around the lives of Nkem, who lives in America, and her husband Obiora who lives in Lagos. The person who gives away Obiora’s infidelity is Nkem’s friend, Ijeamaka – (is she really a friend or simply an “amebo” who derives some pleasure by telling another woman of that woman’s husband infidelity?) The reader should also note that there is a certain deliberate irony in the name of this character which could means in some contexts – It is good to travel/travel is a good thing. Nkem’s pains arise principally from the fact of her separation from her husband caused by her sojourn in the States!

Engaging with this short story brings the reader to experience all the pains of wives of absentee husbands, especially the loneliness and the jealousy of such wives stranded, as it were, in a foreign land. Nkem’s situation is made worse by the fact that she is in an unequal relationship where she relies on her husband to lift her and her family out of poverty. She is torn by jealousy and this jealousy even drives her to her trying to imagine how her rival in Lagos looks like. She even cuts her hair to make it look like Ijeamaka had described the hair style of her husband’s lover looked like. Not that Nkem is an angel as the author makes us realize that she too had had affairs with married men before Obiora came her way. The story of jealousy is told from the point of view of a sympathetic insider including even when pain and jealousy make Nkem discuss her husband’s infidelity with her house girl, Amaechi. Was this necessary, one may ask? Envy can create stress which can then drive us to do crazy things. In the end she takes the bold step of informing Obiora that she intends to relocate to Lagos with the kids to stay with him, an act that requires the recognition and exercise of her agency.

A private experience is the next tale and this story is anything but a private experience. It is the story of two women caught up in the spiral of ethno-religious violence in Kano. Such violence is not unusual in Nigeria where religious zealots hide behind the cloak of religion to unleash senseless violence on their fellow citizens. Some sentences cleverly bring out the economic and political motives behind the mayhem. As the lady tells Chika, the rioters are not going to the small shops but are rather focusing their aggression on the big shops. As the author says, religion and ethnicity are often politicized by the political class to wreak havoc on society. One of the woman caught up in this maelstrom of violence is a lactating mother now separated from her daughter Halima by this sudden eruption of mayhem and carnage. The victims of this violence therefore go beyond our two characters – they include a child deprived of her mother’s milk and Chika who is praying and hoping that her sister Nnedi is not killed in the violence The story is told in the present from a third person perspective but with constant look into the future made possible by the use of “later, she would” or “later this would happen”

Ghosts is a story of loss and coping with loss, but Chimamanda manages to weave a number of related social topics and issues into the story. These include delays in the payment of pensions to retired university staff, the Nigeria-Biafra civil war, a blistering criticism of indecent practices in Nigerian universities starting from abuse of power by university vice chancellors, the unsavoury practices of university lecturers, the scourge of fake drugs to the endemicity of bribery before one can access public services. Running in the background of all of these is the story of a professor who hallucinates and who believes that his late wife Ebere comes to him at night. One conclusion that we can safely draw from this is that the professor is yet to achieve closure on the death of his wife!

On Monday of last week is a story that explores a number of themes – child minding patterns in the USA, the challenges of identity in biracial unions, Immigration challenges and how living apart because of difficulties with obtaining visas to the USA can slowly but surely eat away at the bonds of relationships. It is a story of the troubling issue of a marriage in a drift and where partners are becoming more like strangers to one another and the tragedy in a union where affection gradually dies out. It also hints at the taboo topic of lesbianism as Kamara discovers that she is gradually being sexually attracted to Tracy.. Kamara is the main character, and the story is told from her point of view. She makes powerful statements about parenting in the USA describing it on one occasion as a “juggling of anxieties” that came about from “having too much food”!

Kamara is also capable of very powerful descriptions of people and emotions – one’s “eyes shining with watery dreams”, describing her emotions on her first encounter Tracy, the mother of Josh, the boy she is hired to look after as a “flowering of extravagant hope” and describing Neil (Josh’s father) as a “collection of anxieties”. The relationship between Kamara and Tobechi as undergraduates at Nsukka is described as “filled with an effortless ease”. This contrasts with the emptiness and the “desperate sadness” she now feels because the emotions she wanted to hold in her hands were no longer there. A sad tale indeed.

Jumping Monkey Hill is another story that explores racism and gender and a number of other themes using a writers’ retreat as the canvas on which these are painted. The story explores and challenges white supremacist views on literariness and aesthetics, abuse of power, moral decay and sexual exploitation of females in the banking sector in Nigeria and finally the differences between West Africans and their brothers/sisters from Eastern and Southern Africa in their relationship with persons from the seats of power of their former colonial masters. The story is told from the point of view of Ujunwa, a former bank worker now turned budding creative writer.

Through Ujunwa’s eyes, we witness the corruption and use of female staff of banks as baits to catch clients and secure deposits from these. Her experience with Alhaji is most distressing and the practice as described was a common feature of client sourcing in banks in Nigeria some few years ago. She decides to make this experience the core of her creative writing assignment at the writers’ workshop in jumping monkey hill and is distressed at the dismissive appraisal her effort receives from Edward, the workshop organizer. Edward comes across as someone with a strong colonial hangover as his attitude to the participants at the workshop betrays major strains of patronizing condescension. He also has poorly concealed sexual intentions towards Ujunwa and in this he cuts the figure of an exploitative sexual predator. Other themes touched upon in this powerful story are those of lesbianism and marital infidelity. The former centers on the life of the workshop participant from Senegal who has come out to declare her lesbianism, whilst the latter, marital infidelity, affects Ujunwa’s mum who is abandoned by Ujunwa’s father for a fair complexioned lady, the yellow woman. Peer commentaries at the workshop also afford us a peep into what one could call the rudiments of guides to people attending a creative writing workshop as well as the criteria for aesthetic judgements and evaluations of works of art in prose. Is the writing full of flourishes? Does it have too much energy? Is the narrative plausible? Is the story realistic or is it an instance of agenda writing? Is the style of writing a bit recherché, that is, does it make too much effort to be literary? Jumping Monkey Hill is a great story and the setting in Cape Town makes one wonder the utility of some creative writing workshops, especially those that are nothing else but poorly disguised efforts at cultural imperialism.

The Thing Around Your Neck is another love story involving a biracial couple – Akunna and her white lover. But this love tale is also used to package some of the challenges of immigration, such as Akunna’s sponsor for her visa who tries to take sexual advantage of her, the difficulties Akunna had when she left the house of her sponsor, the challenges of working to earn a living and the exploitation of immigrants by their employers, her efforts to resist the love advances, the prejudice that greeted their relationship when it eventually took off and her decision to travel home on news of her father’s death. Another theme introduced quite early in the story is the huge burden of over-expectation placed on persons who travel abroad by relations and friends. Such over-expectation founded on a too rosy assessment of life in the USA ends up placing huge stresses and strains on the immigrant and could even become like a choking grip on the neck of an immigrant. The story is compelling and is told in an easy-to-read manner from the point of a detached but engaged narrator looking inwards from outside. The thing around one’s neck is an Igbo expression that conveys a deep source of worry which is always there, disturbing and choking and which causes silent but persistent discomfort. As has been pointed out earlier, it could be the cross of having to work in difficult circumstances to be able to meet one’s obligations or it could be an ever-present concern that refuses to go. The collection of stories take the title from this story and the style of writing is so endearing.

The American Embassy is set against the background of one of Nigeria’s most inhuman and cruel military dictatorships. The period was a dark one for Nigeria as individual and press freedoms were trampled upon. The resistance was championed by a loose association of journalists and academics, most of whom sought refuge abroad. The escape route was usually through the Nigeria-Benin border. The security services were most efficient in carrying out acts of repression and suppression and persons who wrote articles critical of this cruel and unimaginative regime did so at the risk of arrest and possible permanent disappearance. It is against this background that this story is set. The security services have come to arrest a journalist who has written something critical of the administration. However, by the time they got home, he had “flown”. In their frustration and in keeping with their modus operandi, they start to harass his family and one of them even goes as far as attempting to sexually harass his wife. In the ensuing tension and confusion, one of the security men shoots and kills the son of the journalist. The description is so real and intense, and the visual imagery is so gripping.

The wife then applies for an American visa and this section of this story is done with so much attention to detail that all the frustrations, psychological traumas and humiliations that persons seeking an American visa in Nigeria come across so forcefully. Can the Americans claim that they are unaware of the humiliations and inhumanity that people go through in their quest for visas? Flogging and beatings of applicants by over active soldiers with obvious streaks of sadism? Can they claim that they are not aware of the difficulties in their interview processes and of some of its opacity?

The story is full of examples of Adichie’s narrative powers. Her description of the area around the American Embassy – the beggars, the petty businesses, plastic chair rentals, the instant photographers etc., bring the place alive as does her description of the blood stain on Ugonna’s shirt as palm oil splash. Adichie also jolts us a little when speaking through the main character in this tale, she suggests that what is described as courage or bravery of the journalists who spoke up the military dictatorships could be a case of exaggerated selfishness. Is this fair? Or was she trying to draw the reader and get him or her to reflect on the basis and full driver of courage when one is confronted by an oppressive regime? The main character’s application for an asylum visa to the USA Is unsuccessful due to important miscommunications between the visa interview officer and the applicant – how fair is it to request a woman who has witnessed her son shot dead by a red eyed security man with alcohol infested breath, a woman who had had to jump out of an upstairs window to escape possible death and rape to provide proof that the assailants/assassins were agents of a repressive government? In the end, the applicant walks away from the interview.

The Shivering is a story of unrequited love set against the context of one of the most disastrous aircraft accidents in Nigeria. The story is set at a time when air travel in Nigeria was so poorly regulated that accidents were very frequent and air travelers travelled with their “hearts in their hands” each time they boarded a flight.

The setting for the story, however, is the USA allowing Adichie to bring up issues that touch on immigration as a side theme in this sad story. Three different love stories unfold as we read along. The ill-fated love between Ukamaka and Udenna is the main course but an important side course is the homosexual rapport between Chinedu and Abidemi. The third love story is the incipient love between Chinedu and Ukamaka, two souls who had been poorly treated in their previous liaisons and who were now united by the common experiences of suffering from unrequited love. Chinedu’s case is worsened by his irregular visa status. Why does Ukamaka persist in her love for Udenna when it is clear that he does not harbor any thoughts of any serious relationship with her? Why does Chinedu cling to his love for Bidemi when it is clear that he is using him and using his economic power to hold him hostage?

The theme of homosexuality is one which Adichie often comes back to and one wonders why. Another theme explored in this short is that of God, religion and religiosity. Why does God allow bad things to happen? When bad things happen, what explanations can we advance for them? Can humans understand the mind and ways of God? Is faith rational? Is faith uncritical in its manifestation? Adichie raises these questions and leaves us to ponder them in our hearts.

The Arrangers of Marriage is another sad story involving a Nigerian resident in America – Ofodile who comes home to pick a bride, Chinaza. It is a criticism of arranged marriages. Adichie is at her best here in her deployment of biting sarcasm, dark humour and ridicule in her portrayal of Ofodile. He comes across as insensitive, uncouth and raw as she slowly allows his personality to unfurl. In a description of a sexual encounter between Ofodile and Chinaza, Ofodile jumps on his new wife allowing her very little or no time to get into the mood. He then gratifies his sexual urge without a thought for her pleasure from the encounter. Sexual engagements of this type can actually be described as rape, even when this is done in a marriage. Chimamanda can be very earthy too in her writing here. An example of such is when she describes the itchy feeling Chinaza has between her legs once Ofodile has satisfied his sexual urge and rolls off without giving a thought to helping his wife to clean up. The author is unsparing in her slow but progressive description, call it characterisation if you will but somewhere along the line, the characterisation begins to read as some slow destruction and dismantling of Ofodile through the strategies of ridicule and portrayals of the inaccuracies in some his claims. And the examples are legion. Ofodile speaks a phony type of American English especially in the presence of whites. And the oddities in his profile and behavior are legion – he rejects his Igbo name, he has been involved in a green card marriage and he is very shallow when it comes to showing proof of emotional intelligence. To imagine that there are Igbo doctors who are this uncouth in the USA makes one shudder. I am even inclined to see Ofodile as a flat character and not a rounded one. His marriage to Chinaza is certainly headed for the rocks and the reader is not surprised when she walks out of her maternal home but is unable to sustain the decision to quit the marriage because of economic reasons suggesting the intersection of female dependence and the perpetration of patriarchy. Is this story an example of feminist writing? I am not sure. Clearly, Chinaza finds herself in a relationship characterized by power asymmetry between and Ofodile. But she had her choices. Should we not hold her accountable for the decisions she takes? She is the story teller and wins our sympathies and she engages in one long unrelenting male bashing. Is male bashing the distinguishing feature of feminist writing? I think not.

Tomorrow is Too Far is about sibling rivalry carried too far and also a critique of male child preference in Igbo society. Nonso is the brother of the main character, a girl whose name is not disclosed. She has taken a childhood fancy to her cousin Dozie. She is very envious of the attention that her brother, Nonso, receives from their grandmother, and in one moment of senseless stupidity, she manages to distract Nonso who has climbed up a tree to harvest some fruits by shouting that a dreaded snake, Echi eteka, was on the tree. Nonso, is frightened and in that moment of fright lets go of his grip, falls to the earth, cracks his skull and dies. The story also touches on mother-in-law and daughter-in-law relationship and tensions, the tensions in this case made even more complex and intense by the fact of cultural differences and distance. Things are also worsened by the fact that Nonso’s parents are separated.

The Headstrong Historian, the last story in the collection treats a number of themes ranging from a condemnation of practice of inheritance in precolonial times, to critique of the way women are treated in traditional Igbo society, to the early contacts between Igbo society and the Christian missions and the unhealthy rivalries between the Catholic and the Anglican missions in their struggle to win converts, to a subtle affirmation of feminism and to a challenge to colonial historiography. The last theme in this story in TTAYN is important as colonialist historiography had done its best to present its military excursions and destructive missions into the territory of the colonized as evidences of events carried out with the noble intention of pacifying the “tribes” inhabiting those areas and thus bring them under the civilizing and beneficial influence of the colonial administration. But this narrative is seriously challenged and debunked by the research work of Anikwena’s daughter, the headstrong historian. To the extent that the historian who does this debunking is a female could be said to be Adichie’s celebration of the triumph of feminism. A combined assault on colonial historiography and aspects of feminism are therefore unleashed in this short story, from the time we are told that Nwamgba threw her brother in a wrestling match to the final unfolding when Nwamgba’s grandchild, a female historian redresses the inequalities and inaccuracies in historiography that the great Chinua Achebe had alluded to in the closing chapter of Things Falls Apart.

Equally engaging is the rich way, the narrator exposes to us the early beginning of Christianity in Eastern Nigeria. Through the eyes of the narrator, we also get to see the tensions that neophytes to the new religion go through, including challenging and even attempting to look down on and even ridicule some of the practices in their own societies which they describe as primitive, thereby showing an uncritical acceptance of the language and judgments of the evangelizers. We get also to catch glimpses of some of the excesses of these new converts, especially those who use their developing linguistic competence in English to even try to pervert the cause of justice. Finally the motivations of converts to the new religions as well as the differences in the approaches to evangelization and the use of Nigerian languages is also brought up and examined, even though the examination is not conducted at the right level. Adichie does not spare her main characters from the lash of her wit, humor and sarcasm. Thus Nwamgba though a convert to Christianity does not hesitate to go and consult the traditional deity in her moment of need, nor does Nwamgba herself spare the agent of the oracle she consults when that oracle asks for a bottle of Gin, among other gifts as a condition for the god to grant Nwamgba her request – and it is this candid portrayal of religious hybridity that adds to the beauty of this particular story. Nwamgba can also be seen as a forerunner of the Igbo feminist in her display of physical strength and her demonstration of agency in her bid to solve problems that impinge on her including the efforts she made to recover her land which the relatives of her husband impound when he passes on. Such harmful traditional practices were rife in the Igbo society where this gripping tale is set.

These twelve stories achieve their purpose with great artistic economy and impact and do not suffer any of the defects of the short story. As is well known, a major challenge with the short story as a genre is achieving adequate characterization for the personae in such stories for their utterances and actions to achieve plausibility. Most short stories therefore suffer from some form of lack of depth in their main characters. However, the characters in these twelve stories have none of those defects as they come across as fully fledged, rounded and plausible characters of the type you could come across in real life. TTAYN is thus a great book and an important contribution to our stock of short stories in Nigeria and indeed in Africa. It is even made richer by the use of linguistic devices to present the stories and the characters in them. The use of the second and third person narrative approach enriches the story as does the way, Adichie, a consummate story teller starts a story some times from the middle and then keeps shuttling between time past and present to make the story come fully alive.

TTAYN is a collection of great short stories that examine a number of real issues and challenges – love, infidelity, envy, race, corruption, coping with loss, political violence, religion, colonialism, domestic violence, harmful traditional practices, exploitation, sexual orientation and power asymmetries in relationships etc. It is a book that I would certainly encourage anyone anxious to experience some of these themes as seen and presented by a story teller with plenty of empathy and wit to read.